Sunday, April 18, 2010

- 2009-2010 Season

- Symphony Orchestra

- Conductor: Jed Gaylin

- Works Performed:

- Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, Op. 63 by Sergei Prokofiev

- Canzon a 12 by Giovanni Gabrieli

- Symphony in D Minor by Cesar Franck

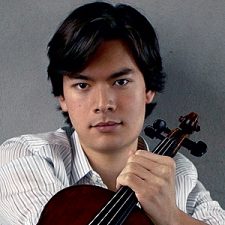

- Featured Artists: Stefan Jackiw

Concert Details

Program Notes

Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor, Opus 63

Allegro moderato

Andante assai

Allegro, ben marcato

Serge Prokofiev

(born Sontsovka, Ukraine, 1891; died Moscow, 1953)

Prokofiev’s marvelous, somewhat quixotic Violin Concerto No. 2 bears the telltale signs of a composer in transition, both ideologically and geographically. The piece was commissioned for the French violin virtuoso Robert Soetens by a group of his admirers. The work was completed and premiered in 1935. At the time, Prokofiev was gradually repatriating himself to Moscow after more than two decades of building his career as a composer, conductor, and pianist in the West. He was shedding some of his ferocious modernism and actively embracing the new Soviet musical aesthetic of simplicity and lyricism.

He composed the concerto while touring the world. As he recalled in his autobiography, he wrote the first theme of the first movement in Paris, and the main theme of the second in Voronezh; he completed the orchestration in Baku; and the piece was premiered in Madrid. The music itself is equally peripatetic, harboring multiple personalities: lyricism, anxiety, sarcasm, naiveté, wildness, and the feeling that, given the right nudge, we might just witness all hell breaking loose.

The concerto also marks an important point in Prokofiev’s evolution as a composer. Immediately after completing it, he set to work on his ballet Romeo and Juliet and his Symphony No. 5, two 20th Century masterpieces. The ballet’s lyricism, those exotic, charming melodies, appear to have had the violin concerto as their drawing board. Certainly, the beautiful theme in the concerto’s second movement foretells the dances of the star-crossed lovers. Likewise, the massive sonic canvases that occasionally take over the concerto seem to have gotten fully worked out in the fifth symphony. Prokofiev so delights in percussive color that parts of the concerto’s first and third movements might rightly be considered a concerto for violin, bass drum, and orchestra, and the castanets that accompany the third movement’s main violin theme seem to have set the stage for the fifth symphony scherzo’s delicious percussion extravagance.

Of all of the concerto’s curious, delightful, and exciting elements, the solo violin delights the most. From its dark and longing opening theme, through the second movement’s soaring pure melody, to the witty and sarcastically jangled dance-like third movement, the violinist gives the concerto’s many personalities their voices.

Canzon à 12

Giovanni Gabrieli

(born Venice, c1553-6; died Venice, 1612)

In a lagoon that stretches into the storied Adriatic Sea rises the magical city of Venice, and at its heart stands the majestic St. Mark’s Basilica. For centuries, Venice was the center of the known universe, hosting visits from the world’s most important achievers, and sending off its mighty fleets to every corner of the globe. The Basilica’s almost mystical opulence, rivaling that of St. Peter’s in Rome, houses ancient treasures, apparently including the bones of St. Mark the Evangelist himself. The interior is crammed with masterpieces of Venetian High Renaissance art. Above, domed ceilings rise to the heavens, sparkling with some 86,000 square feet of gold-leaf mosaics. Just below the gold-twinkling heavens jut multiple choir lofts. It was for this space that Giovanni Gabrieli wrote his greatest music. Undoubtedly, it was for one of St. Mark’s special occasions that he composed his Canzon à 12.

Gabrieli served as St. Mark’s principal composer from 1586-1606. Besides writing and organizing sacred music for the Basilica, his responsibilities included composing for Venice’s many special festivals and head-of-state visits. His music represents the pinnacle of High Renaissance composition. His canzoni (roughly meaning “songs,” derived from the French/Dutch chanson) are as exciting to hear today as they were 400 years ago.

Gabrieli wrote the Canzon à 12 for 12 brass instruments in three unmatched “choirs”:

Choir I: 2 trumpets, 2 trombones

Choir II: 2 trumpets, 1 trombone

Choir III: 1 trumpet, 2 French horns, 1 trombone, 1 bass trombone

He spread the three choirs across three different lofts in the Basilica, and had them play separately (“call and response,” antiphonally) or together in unison. Most canzoni had several short themes played in imitation, canon (round), or fugue, each group’s theme echoed and challenged by the others’. The result is a complex, often syncopated tapestry of intricate sound. Gabrieli excelled in his inventive themes and their harmonies, his remarkable craft at blending them in counterpoint, and his brilliance in varying tempos, time signatures, and dynamics. The first listeners must have been dazzled as the sounds of the Canzon came at them from every direction in the glorious spaces of St. Mark’s.

Symphony in D Minor

Lento, allegro non troppo

Allegretto

Allegro non troppo

César Franck

(born Liège, [then] Belgium, 1822; died Paris, 1890)

Of the relatively few symphonies to come out of France during the 1800’s, it’s ironic that Franck’s Symphony in D Minor should be one of the crown jewels. To begin with, it was his only mature attempt at a symphony, and he had to be persuaded by his organ students to write it. In 1886, when he began, Paris was still crazy for opera — a genre that Franck had attempted several times without success. On top of that, the symphony’s 1889 premiere performance was awful. Worse yet, essentially everybody who was anybody in Paris’s petty and political musical circles hated it. Charles Gounod said that the piece showed “incompetence driven to dogmatic lengths.” Franck died the next year, believing the work a failure. As unlikely as its success should have been after all that, within a year after his death his symphony began winning admirers far and wide, and has done so ever since. We love it for two main reasons: The writing is intelligent but completely accessible, and its beauty and enthusiasm are undeniably sincere.

Franck’s musical heroes were Bach, Beethoven, his lifelong friend Liszt, and, to a lesser degree, Wagner. It comes as no surprise, then, whence Franck derived his brooding, unresolved three-note opening motif, the seed of the entire work. A similar three-note motif begins the finale to Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 16, Op. 135, a stirring work on whose score, above those three notes, Beethoven wrote the cryptic message, “Must it be?” Liszt used this motif as a central musical figure in his Les Préludes, and Wagner used it in his Ring Cycle as the leitmotif for fate. Unlike Liszt and Wagner, Franck does not tie the motif to a story line. Rather, in the German classical tradition, he presents the theme and develops it. Still, his symphony is a Romantic creation, rich with deep emotion, gorgeous chromatic harmonies, and a clever structure.

Franck opens the symphony with his three-note motif at a slow pace, building it into a mysterious, almost religious, introduction and then speeding it into an allegro. He introduces a new melody in full orchestral grandeur, dispelling the brooding nature of the opening. His brilliant orchestration lets you hear individual voices within the full, grand texture, like an organ. The mysterious mood returns briefly before a brief coda ends the movement with roaring brass and a glorious shift into D Major.

This symphony has only three movements, instead of the usual four. Franck cleverly combines the expected slow second movement and the fast scherzo third movement into one. He begins with harp and strings plucking what sounds like the accompaniment to an antique carol or hymn. The English horn enters with an exquisitely lyrical theme whose first three notes are a slightly altered version of the symphony’s main motif–. Franck then embeds a contrasting scherzo. He ends the movement with the English horn and the scherzo joining together for some fresh and beautiful counterpoint.

The last movement is a prime example of what has been termed “cyclical form,” a recycling of all of the symphony’s earlier themes to unify the work. Franck is generally regarded as the master of cyclical form, though here he is paying homage to his musical heroes. Beethoven did the same in both his fifth and ninth symphonies, and Liszt stocked his compositional career on the idea. Franck brings his themes together with a joyful exuberance. Even as he brings back the mysterious introductory theme from the first movement, with that famous three-note motif, he manipulates it in a way that makes us feel as though the curtains are being drawn aside and golden light is about to burst forth. Again like mountains of sound from an organ, brass and full orchestra blaze brilliantly into the final chords.

Program Notes by Max Derrickson